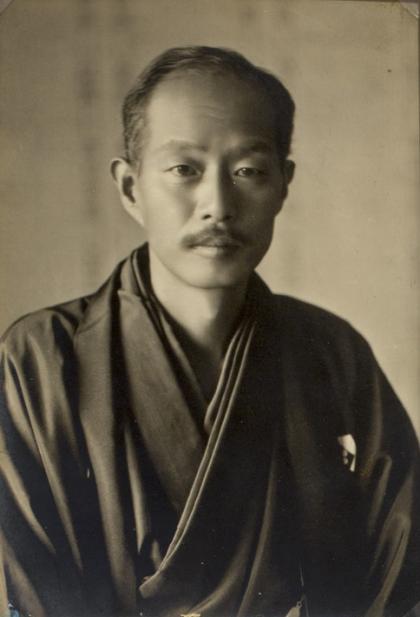

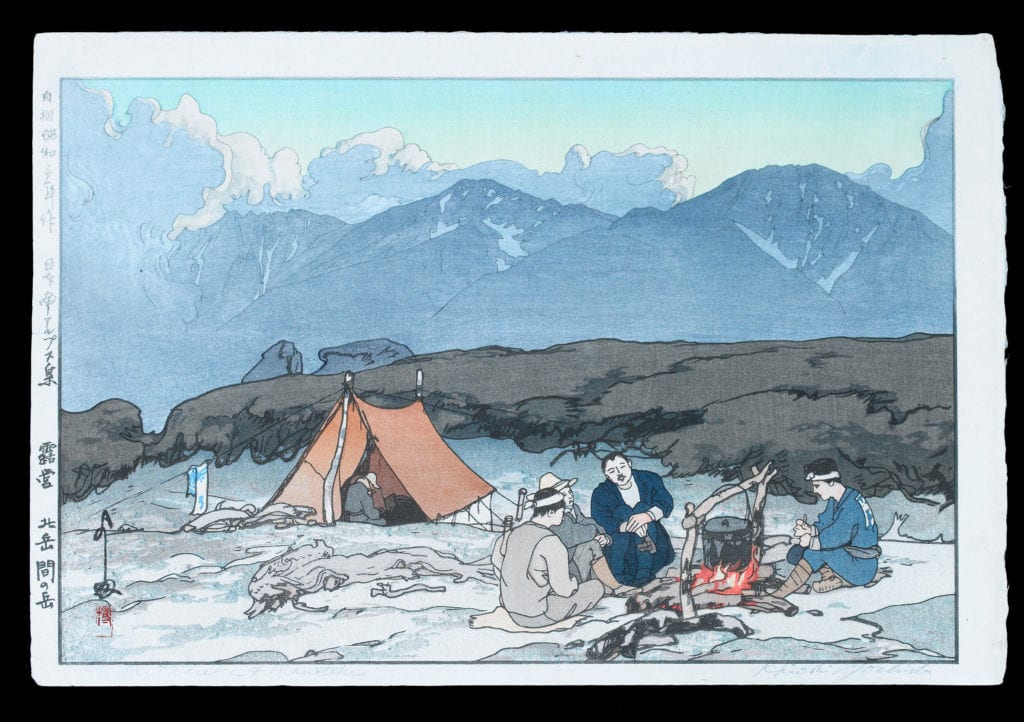

My eyes lit up when this piece came in—one of the most prized prints by the great shin-hanga printmaker Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950) whose work I love and love to frame (and even named a frame design for). Yoshida was a mountaineer, so it’s no surprise that some of his most beautiful and reverential images are of mountains. “Grand Canyon,” (1925, oban size, 9-3/4″ x 15″) is an inspiration—and inspired me as a perfect opportunity to try out a kind of joinery I’d been playing with on paper: a decorative dovetail.

I don’t generally find the shape of a dovetail natural to picture frame joinery, at least when it’s visible on the face. But this is one instance where it felt perfect, offering a lovely way to marry the Japanese to the American Southwestern—the kind of fine wood joinery so highly developed in Japan with the patterns of Southwest Indian weaving culture, patterns that themselves resonate with the iconic geological forms and strata of the Grand Canyon, which Yoshida captured so beautifully in the print.

As I’ve discussed before on the blog, given the material the two art forms have in common, there’s a natural harmony between wooden frames and woodblock prints. Carefully designed and executed, the frame on a woodblock is an opportunity to sustain and amplify the picture’s effective traits.

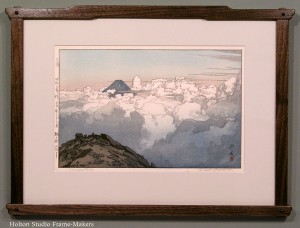

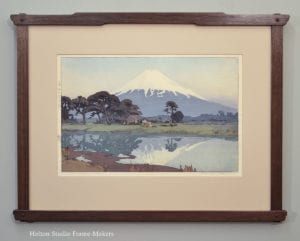

This walnut frame is proportioned the same as our typical Yoshida frame that we make for oban size prints: the top and bottom are 3/4″ wide, the sides 1″. (The outside dimensions of the frame are 18″ x 22-1/2″ through the centers.) The profile too is the same as the Yoshida’s—a simple square with crisp edges. The decorative detailing is in the joint itself, which is a modified dovetail with a kind of haunch; and like the Yoshida, the horns are extended a little, in this case effectively repeating the strong theme of horizontal lines in the print, but here I’ve cut them with a decorative zig-zag pattern. The joinery and decorative cuts were both done with a Japanese dovetail saw and chisels—a fact that illustrates a principle I hold dear, which is that there is no hard line between the purely “functional” or “practical” work of joinery and the “artistic” work of decorating. Completing the frame is a little 1/8″ walnut slip, given a black wash to contrast with the frame and repeat the print’s line work.

and like the Yoshida, the horns are extended a little, in this case effectively repeating the strong theme of horizontal lines in the print, but here I’ve cut them with a decorative zig-zag pattern. The joinery and decorative cuts were both done with a Japanese dovetail saw and chisels—a fact that illustrates a principle I hold dear, which is that there is no hard line between the purely “functional” or “practical” work of joinery and the “artistic” work of decorating. Completing the frame is a little 1/8″ walnut slip, given a black wash to contrast with the frame and repeat the print’s line work.

We used an 8-ply mat for the stronger line its bevel would create compared to that of a more typical 4-ply mat. Its deep bevel also repeats the stepping perspective of the scene and the angular forms of the mountains. The solid core rag mat is a muted tan with the subtlest hint of green that’s a perfect cool complement to the print’s warm pinks and oranges.

Spelling it all out that way makes it seem like a lot of details to what should be a simple presentation. But the approach is consistent with and suited to the amount of fine detail and care in the print, and subtle enough that it remains appropriately subordinate to the picture even as it fully honors it. I’m especially pleased with the subtlety of the dovetails.

Spelling it all out that way makes it seem like a lot of details to what should be a simple presentation. But the approach is consistent with and suited to the amount of fine detail and care in the print, and subtle enough that it remains appropriately subordinate to the picture even as it fully honors it. I’m especially pleased with the subtlety of the dovetails.

One of my favorite discoveries as I’ve explored the art of the picture frame is the effectiveness of joinery. I’m convinced that joinery is something we’re drawn to instinctively, and that its natural attraction for us is due to the very nature of the arts that are the essence of our humanity—the word art, Merriam-Webster’s dictionary tells us, being rooted in the Latin ars, meaning “to join.” We are homo faber; we make things, which means we put things together. And in that work we bring together—we join—head, heart, and hand. The well-made frame is a perfect example of how there is no sharp line between “functional” and “artistic” work. Just as there is no sharp distinction between the structural and decorative function of a dovetail joint, there is no sharp distinction between “functional” and “artistic” work. They both flow with the common spirit of care. The well-made frame both protects and celebrates the picture, both aspects born of the same heart that cares for the picture. Care is beautiful.

Furthermore, the instinctive appeal of joinery extends to the relationship of frames to pictures—to all the arts to each other, for that matter: they are most effective, most compelling and beautiful, when they are joined together, in cooperation and harmony (another word rooted in the Latin word meaning “to join.”)

The arts are how we join the world and discover and take part in its harmonies—as a Japanese mountaineer and artist joined his culture’s tradition of printmaking to the landscape and culture of the American Southwest; as a nearly hundred year old print is given a fitting place in our time; and as patterns created by and associated with the arts of two distant places can come together in the living art of the picture frame.

Other Hiroshi Yoshida mountain prints (3 we’ve framed + 1)—

« Back to Blog

A really intriguing joinery solution and beautiful execution. The design not only echoes the motif of the print but also a sense of the cultural motifs of the indigenous people of the Grand Canyon.

Thanks for the exceptional article and artwork.