Believed to date from the 1880’s, this 12″ x 18″ painting of the last light of day is from the brush of George Inness (1825–1894). We’ve made a few frames like this one, and the design seemed to me perfectly suited to Inness’s gentle and lush grassy hills. Constructed in quartersawn white oak, the 3″ wide frame is a compound, a simple carved cushion complemented by a narrow carved cove inner molding. The back of the frame is cut in and then sweeps out beyond the outside of the frame’s face. The frame is fumed and stained. A bronze slip seems to catch the vanishing sunlight. Trevor Davis made the frame, and Sam Edie finished it. The painting is available from California Historical Design. [UPDATE: This painting has sold.]

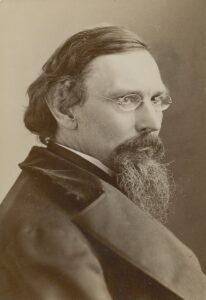

William Keith once called Inness “the biggest man in America,” and he wasn’t alone in his estimation of Inness’s significance to the nation’s landscape painting tradition and therefore its culture.

William Keith once called Inness “the biggest man in America,” and he wasn’t alone in his estimation of Inness’s significance to the nation’s landscape painting tradition and therefore its culture.  Some have called Inness the father of American landscape painting, but that would seem to ignore the Hudson River School, which began a generation earlier to established a formidable landscape painting tradition in this country. Inness himself started out closely studying Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. But after a trip to Europe that exposed him to the French Barbizon painters, Inness brought to the American scene a more intimate and mystical approach that, at least for some, eclipsed in influence and significance the grand vistas of the earlier painters.

Some have called Inness the father of American landscape painting, but that would seem to ignore the Hudson River School, which began a generation earlier to established a formidable landscape painting tradition in this country. Inness himself started out closely studying Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. But after a trip to Europe that exposed him to the French Barbizon painters, Inness brought to the American scene a more intimate and mystical approach that, at least for some, eclipsed in influence and significance the grand vistas of the earlier painters.

But if Inness is not the father of American landscape painting, he’s certainly the father of American Tonalism. (The younger James McNeill Whistler had quite a lot to do with it as well, but from a very different set of ideals.) Inness was deeply religious and philosophical, and sought to express on canvas the insights of the eighteenth century visionary Emanuel Swedenborg. Of special importance to Inness was Swedenborg’s philosophy of “correspondences,” summed up by the theologian’s saying “as above, so below” (borrowed from the old Hermetic texts), which posited that the material plane directly corresponds to the spiritual; and “spiritual influx,” painstakingly elaborated in texts such as “Interaction of the Soul and Body” but summarized as, “The spiritual clothes itself with the natural, as a man clothes himself with a garment.”* Thus, to contemplate the natural world was to contemplate the holy spirit and its all-permeating, unifying power in the natural creation. Among other effects on Inness, this vision led the painter to work in close tonal harmonies—thus the label Tonalism—exemplified by this picture. Sunlight corresponds to spiritual light, harmonizing in this still evening a well-nourished patch of landscape fed by the clear pool at its center (its reflections perhaps illustrating the principle of “correspondences”).

The remarkably timeless quality of this painting makes it easy to forget that the entire twentieth century and then some stands between us and Inness’s life. That distance has left us somewhat numb to the turmoils of the late nineteenth century, and in turn to the profound significance of landscape painting to that rapidly industrializing and urbanizing age. Shifting their homes to cities, their work to factories, and their attention to consuming an unprecedented quantity of new products, Americans had begun that great project of transforming their civilization (although Mark Twain among others would mock its claim to that ideal). We’d undertaken to construct a human-made shell around our lives—replacing the eternal frame of nature with a man-made frame. And with traditional rural communities breaking up, daily labor made more divided and specialized than ever, and consumerism magnifying the desires and significance of the individual, life was fragmenting.

The remarkably timeless quality of this painting makes it easy to forget that the entire twentieth century and then some stands between us and Inness’s life. That distance has left us somewhat numb to the turmoils of the late nineteenth century, and in turn to the profound significance of landscape painting to that rapidly industrializing and urbanizing age. Shifting their homes to cities, their work to factories, and their attention to consuming an unprecedented quantity of new products, Americans had begun that great project of transforming their civilization (although Mark Twain among others would mock its claim to that ideal). We’d undertaken to construct a human-made shell around our lives—replacing the eternal frame of nature with a man-made frame. And with traditional rural communities breaking up, daily labor made more divided and specialized than ever, and consumerism magnifying the desires and significance of the individual, life was fragmenting.

Little wonder that this painting seems so timeless. Such harmonizing visions were then, and remain now, an antidote to discordant times.

I’m not sure how much Inness weighed in on the art of the frame. As many (though not all) artists of the time did, he probably regarded the fate of his works, once they left his studio, to be out of his hands. This would include the frames that dealers and buyers chose to set them in. The contrast—or conflict—between Inness’s ethos and that of his age is often glaringly clear, for example in this work at right recently sold at auction. A painting is distinctly the artist’s vision; it’s his or her appeal to the world. Its frame is the world’s response to that appeal—or failure of response. The task of today’s frame maker who’s lucky enough to have a work of Inness’s come his or her way is to respect its essence and to provide it with a setting that sustains that unifying, harmonizing, and reverent vision.

I’m not sure how much Inness weighed in on the art of the frame. As many (though not all) artists of the time did, he probably regarded the fate of his works, once they left his studio, to be out of his hands. This would include the frames that dealers and buyers chose to set them in. The contrast—or conflict—between Inness’s ethos and that of his age is often glaringly clear, for example in this work at right recently sold at auction. A painting is distinctly the artist’s vision; it’s his or her appeal to the world. Its frame is the world’s response to that appeal—or failure of response. The task of today’s frame maker who’s lucky enough to have a work of Inness’s come his or her way is to respect its essence and to provide it with a setting that sustains that unifying, harmonizing, and reverent vision.

It’s notable in relation to the subject of this painting we framed that when Inness died while visiting Scotland in 1894 he was watching the sunset. According to his son, who was accompanying him, Inness “threw up his hands into the air and exclaimed, ‘My God! oh, how beautiful!’,” then collapsed and in minutes was dead.

Find both an excellent biography of George Inness and a gallery of his paintings on Wikipedia…

* Van Gogh reportedly said that “A picture without a frame is like a soul without a body,” or, in other words, the picture is to the frame as the soul is to the body. It’s a metaphor that would seem consistent with Swedenborg’s description of spiritual influx: “The spiritual clothes itself with the natural, as a man clothes himself with a garment… [T]he spiritual is within the natural as the fibre is within the muscle, and as the blood is within the arteries; or as the thought is within the speech, and the affection in sounds; and it makes itself felt by means of the natural.… [T]here is only one life, and this is not capable of being created, but is eminently capable of flowing into forms organically adapted to its reception. Such forms are each and all of the things in the created universe.” —From Emanuel Swedenborg, “Interaction of the Soul and Body”.

« Back to Blog