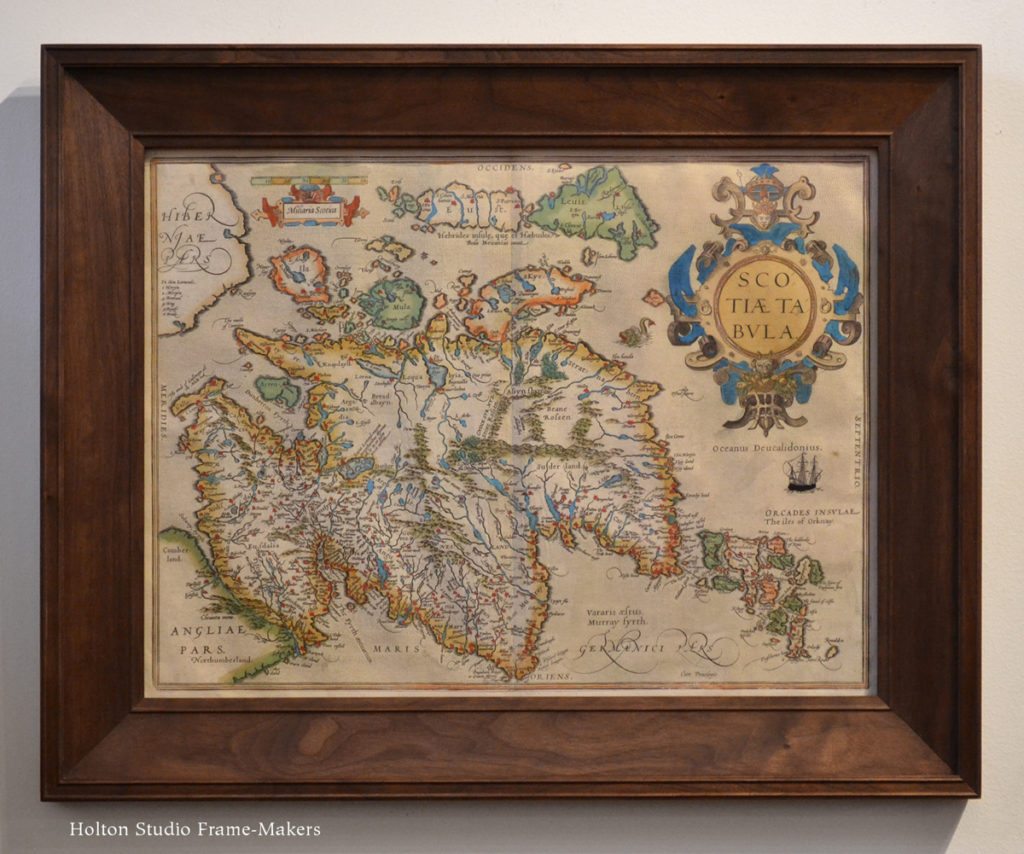

My last two posts were about two jobs we recently did framing antique maps, both featuring carved frames. (The posts are here and here.) Today’s post features two wonderful old maps of Scotland, both in frames that are not carved, but with which I’m no less pleased. Both are in compound mitered frames. The first, dating to the early 17th century, is about 15″ x 20″. It’s in a walnut slope, No. 208 + Cap 188 that’s 2-1/2″ wide. The second map is considerably bigger—about 26″ x 42″. We put it in a similar finely beaded compound mitered frame, No. 108 + Cap 328, but this one is a flat rather than a slope, and made it in quartersawn white oak (with Dark Weathered Oak stain).

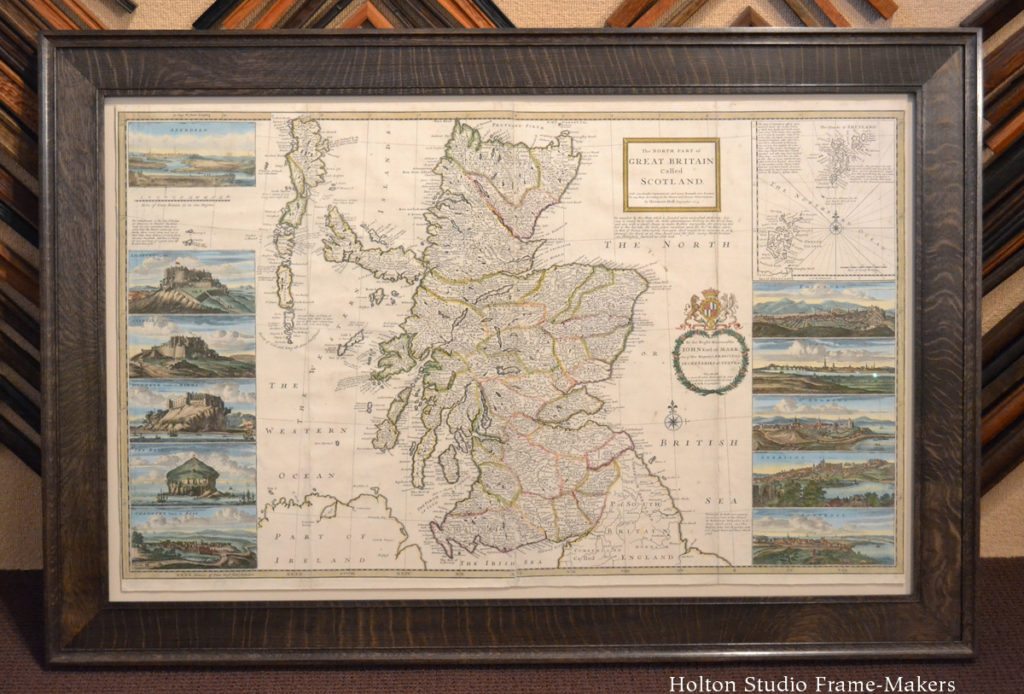

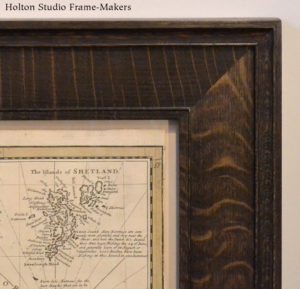

The second map is considerably bigger—about 26″ x 42″. We put it in a similar finely beaded compound mitered frame, No. 108 + Cap 328, but this one is a flat rather than a slope, and made it in quartersawn white oak (with Dark Weathered Oak stain).

Whereas the last two posts showed carved patterns and the use of such decorative work to celebrate the picture, these are more direct presentations, with the frame’s shape reflecting and underscoring the fine line work and lettering. The choice of beautifully figured wood and the suitability of the profile also meet our standard of framing to celebrate the picture, but subordinate that to the more utilitarian standard of straightforward presentation.

Whereas the last two posts showed carved patterns and the use of such decorative work to celebrate the picture, these are more direct presentations, with the frame’s shape reflecting and underscoring the fine line work and lettering. The choice of beautifully figured wood and the suitability of the profile also meet our standard of framing to celebrate the picture, but subordinate that to the more utilitarian standard of straightforward presentation.

This second map was made just a little more than a century after the one above it, and it’s fascinating to compare the the two in terms of accuracy and character of illustration. The second one is a folding map made for travelers to carry. During the seventeenth century populations had become far more intrepid and mobile, as well as engaged in much more far-flung trade.

Maps are an extraordinary reflection and expression of humanity’s relationship to geography—to its life on the earth. And significant as they are, antique maps, which illustrate not only where things are but where people have been and have longed to go, deserve thoughtful and sound preservation and presentation in how they’re framed.

« Back to Blog