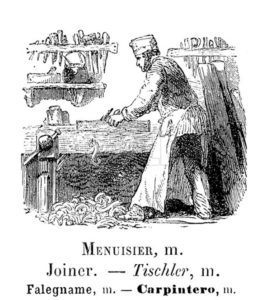

This Labor Day I want to pause to pay tribute to the type of laborer called a joiner. Possibly you’re not sure what I mean by a joiner; the term is more common in Britain than it is here in the states. In the U.S., when we call someone a joiner we usually mean he or she is given to joining clubs and organizations. But that’s the Oxford English Dictionary’s second definition of joiner. The first definition describes the joiner I’m talking about: “A person who constructs the wooden components of a building, such as stairs, doors, and door and window frames.” Wikipedia says, “A joiner is an artisan who builds things by joining pieces of wood, particularly lighter and more ornamental work than that done by a carpenter, including furniture and the ‘fittings’ of a house, ship, etc.”

A few years ago I was startled to see that the Wikipedia entry for “Joiner” noted that, “The terms joinery and joiner are obsolete in the USA.” What was distressing to me about this is that here at the studio our first and most fundamental concern is with the craftsmanship of our frames, and one of their key aspects that we feel sets them apart from conventional frames offered today is their joinery. We work in the tradition that could be called “joiners’ frames,” but is generally called “cabinetmakers’ frames.” And so we are ourselves members of that trade called joiners. I’ll tell you it is not reassuring to find out that according to the esteemed authority of Wikipedia you and the livelihood you aspire to are obsolete.

A few years ago I was startled to see that the Wikipedia entry for “Joiner” noted that, “The terms joinery and joiner are obsolete in the USA.” What was distressing to me about this is that here at the studio our first and most fundamental concern is with the craftsmanship of our frames, and one of their key aspects that we feel sets them apart from conventional frames offered today is their joinery. We work in the tradition that could be called “joiners’ frames,” but is generally called “cabinetmakers’ frames.” And so we are ourselves members of that trade called joiners. I’ll tell you it is not reassuring to find out that according to the esteemed authority of Wikipedia you and the livelihood you aspire to are obsolete.

So while Labor Day seems to most people to have more to do with mourning the end of summer than with celebrating labor, I’d like to take a moment to celebrate the labor of joinery and the laborers called joiners. Forgive me if this sounds self-serving, but I hope you’ll make allowances on Labor Day for an honest laborer trying only to save himself from obsolescence.

The Original Frame-Maker as Joiner

The first frame-makers were joiners. In this role they were naturally honored by anyone who cared anything about the arts. They were not only engaged as a matter of course in the making of frames but were understood by all as being indispensable to and instrumental in the protection, support, enhancement, and honor of the finest of the fine arts, painting—and full participants in the older and more popular understanding of the whole noble realm of human labor—a realm once synonymously called the arts.

Fourteenth century integral painting and frame (The Honolulu Museum of Art)

This was not just an idea. In reality, the first paintings were murals, and often the walls were timber-framed—that is, the work of joiners. And the first easel paintings were on boards joined and prepared by joiners, with edges raised to form an integral frame, or molding permanently joined to the panel. Before the western world made up the false distinction between art and labor (or craft), and between artist and artisan, painters and sculptors came up through the ranks of, and closely collaborated with, other artisans—most closely with those who built the altars and other frames and supports for their work. Naturally, then, they held the arts in general in reverence. Giotto’s tribute to the arts that encircles the base of the Campanile in Florence is just one of innumerable medieval examples of fine artists depicting and thereby honoring artisans, including joiners, and their workshops.

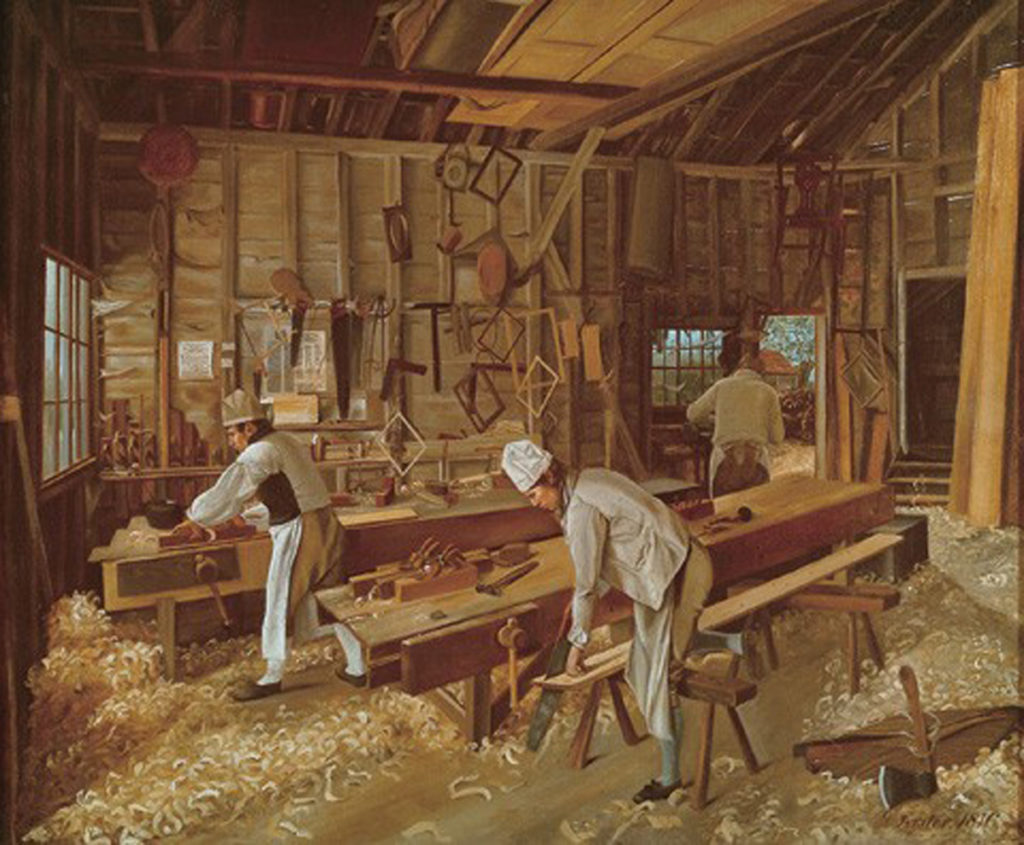

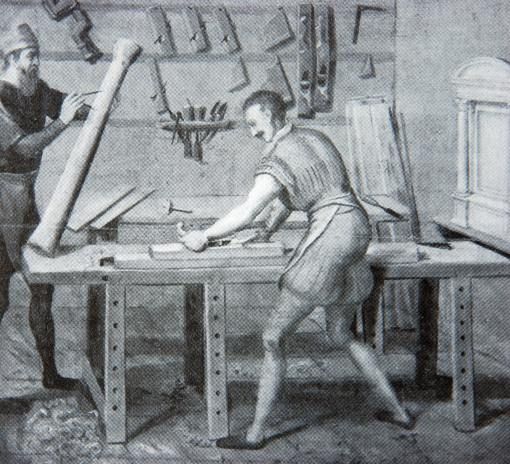

A recent post on Lynn Roberts’s wonderful The Frame Blog includes this much later example below, an 1816 painting by George Forster, which depicts an English joiner’s workshop. Note the many frames hanging on the walls.

George Forster, “English Joiners at Work,” 1816

Wise painters have always understood that their own work and honor as artists depended on the public’s admiration for all the arts, often, naturally enough, beginning with the art most immediate to their own: the picture frame. This was not a matter of mere duty or principle. A painting, every painter knew, depended on a well-made frame to provide its due place—to properly complement, present and enhance as well as protect and support it. And true artists have always known that all labor offers opportunity for invention, thought and expression. Of all the trades, the work of the joiner has not only been closest to the fine art of painting, but serves as an exceptionally illuminating window on the degradation of such labor through its separation from what became only relatively recently, in historical terms, that exalted realm we call Art.

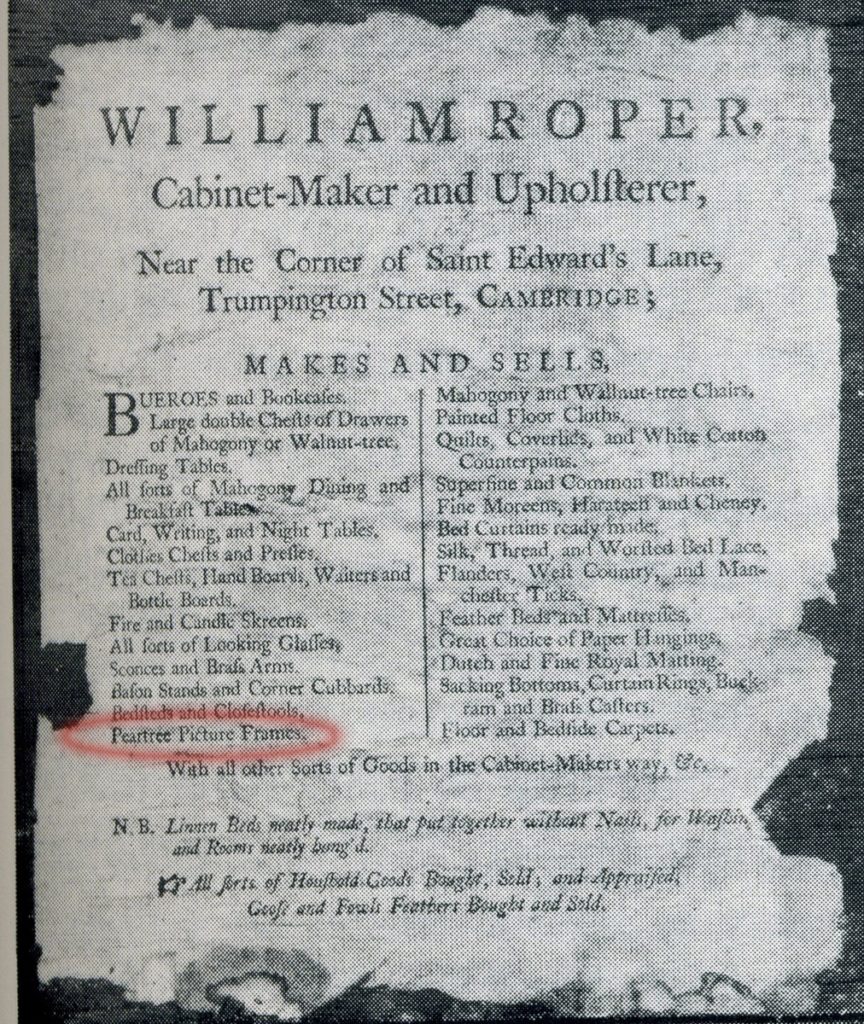

This oak chest is what we’d expect as typical of the work that, prior to the industrial revolution, the town joiner produced. But as we can see from the label inside the lid, shown below, such a workman would also offer “Peartree Picture Frames”—i.e. frames made out of pear wood (which is similar to cherry and was usually stained black, or “ebonized” to look like the ebony frames favored by the Dutch Masters). Also note the pride shown in proper joinery as the joiner William Roper describes another specialty, “Linnen beds neatly made, that put together without Nails…” The pegs at the joints of the chest itself ably advertise the same point: that he does his work well—with care.

This oak chest is what we’d expect as typical of the work that, prior to the industrial revolution, the town joiner produced. But as we can see from the label inside the lid, shown below, such a workman would also offer “Peartree Picture Frames”—i.e. frames made out of pear wood (which is similar to cherry and was usually stained black, or “ebonized” to look like the ebony frames favored by the Dutch Masters). Also note the pride shown in proper joinery as the joiner William Roper describes another specialty, “Linnen beds neatly made, that put together without Nails…” The pegs at the joints of the chest itself ably advertise the same point: that he does his work well—with care.

The Medieval Joiner

William Roper and George Forster’s joiners were the direct descendants of the workmen in the two medieval depictions, below, both of which include frames. The first one, in which the craftsman’s shop is a stall with wares displayed on a counter out front, offered directly to customers, underscores another important line in Mr Roper’s advertisement: “Makes and Sells.” There’s no middle man; maker and seller are joined in one person. Furthermore, the typical customer, in a society where nearly everyone plied a trade, was another artisan. Thus direct mutual provision, named and framed by the word commerce (meaning reward together)—that primal activity of civilization—joins members of the community. The enhanced care that comes naturally to the artisan when dealing directly with the customer subtly but surely infuses the quality of the work. As the Arts and Crafts architect WR Lethaby would write centuries later, “Every work of art shows that it was made by a human being for a human being. Art is the humanity put into workmanship, the rest is slavery.”

From a medieval German manuscript. Note the frame leaning on the left side of the joiner’s stall. (Credit to http://nuernberger-hausbuecher.de/)

These are pictures from a world for which the dictionary definition (in a dictionary dated 1507) of “artist” was synonymous with “artisan”:

These are pictures from a world for which the dictionary definition (in a dictionary dated 1507) of “artist” was synonymous with “artisan”:

“1. One who practices some mechanic art or craft; an artisan. 2. One who professes and practices an art in which science and taste preside over the manual execution. 3. One who shows trained skill or rare taste in any manual art of occupation.”

The accomplished joiner’s work, as with “any manual art of occupation,” was never purely mechanical and functional but involved matters of “science and taste”—matters later extracted and exiled from such trades. Through the middle ages, the joiner’s trade entailed carving, marquetry, turning, and other decorative work. (All of these medieval images here and below, are, like George Forster’s painting, tributes by painters and illustrators to the joiner’s trade.) If you could use a chisel well enough to cut a dovetail or mortise-and-tenon joint, you could certainly carve simple decorations and possessed at least the rudiments of the manual dexterity needed to carve and sculpt more elaborate designs. A great illustration of this seamless relation between the “mechanical” art of joinery and the “fine” art of sculpture is painted on a member of the late twelfth century Spanish cathedral at Teruel; among workers doing typical joinery we find, on the left of the center row, a joiner carving an eagle’s head. Jean Bourdichon’s 15th century miniature, below, also shows the medieval joiner as an impressive carver.

The accomplished joiner’s work, as with “any manual art of occupation,” was never purely mechanical and functional but involved matters of “science and taste”—matters later extracted and exiled from such trades. Through the middle ages, the joiner’s trade entailed carving, marquetry, turning, and other decorative work. (All of these medieval images here and below, are, like George Forster’s painting, tributes by painters and illustrators to the joiner’s trade.) If you could use a chisel well enough to cut a dovetail or mortise-and-tenon joint, you could certainly carve simple decorations and possessed at least the rudiments of the manual dexterity needed to carve and sculpt more elaborate designs. A great illustration of this seamless relation between the “mechanical” art of joinery and the “fine” art of sculpture is painted on a member of the late twelfth century Spanish cathedral at Teruel; among workers doing typical joinery we find, on the left of the center row, a joiner carving an eagle’s head. Jean Bourdichon’s 15th century miniature, below, also shows the medieval joiner as an impressive carver.

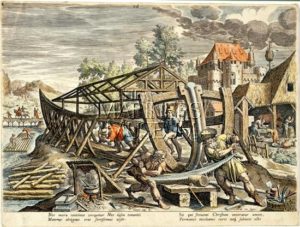

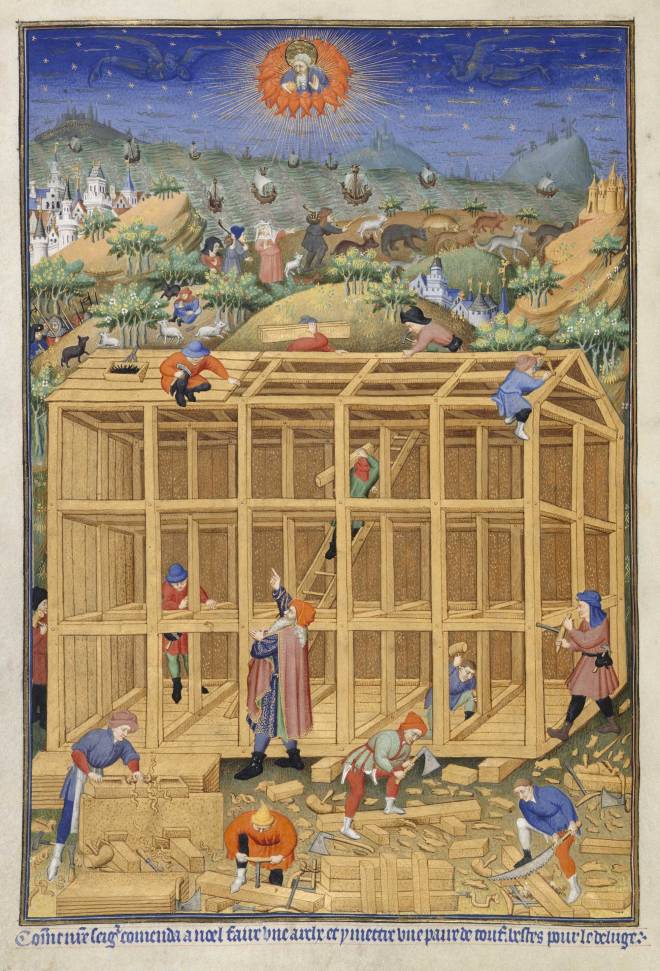

But the scope of work joiners did has to be noted here, because it is highly significant to a true understanding of the nobility of the trade. As the detail from Teruel, above, shows, the medieval joiner’s work included not simply cabinetry, doors, windows and furnishings but the construction, the framing, of buildings. A joiner was also an expert type of carpenter, skilled and knowledgeable in better joining methods than can be had with a hammer and nails; he was a builder. And in an age of timber framing, a master joiner might even be a master builder—or, to use another word for the same thing, an architect. And with such a varied and broad engagement in the great cooperative art of architecture, the joiner joined not only “pieces of wood” but the whole vast and varied range of trades necessary to building, from the basic structure to its finest details including its painted details. Such work brought what we today might consider an ordinary laborer, specialized and therefore likely to be narrow-minded and hide-bound, in very practical and meaningful touch with a great variety of tradesmen and their varied talents and experience.

But the scope of work joiners did has to be noted here, because it is highly significant to a true understanding of the nobility of the trade. As the detail from Teruel, above, shows, the medieval joiner’s work included not simply cabinetry, doors, windows and furnishings but the construction, the framing, of buildings. A joiner was also an expert type of carpenter, skilled and knowledgeable in better joining methods than can be had with a hammer and nails; he was a builder. And in an age of timber framing, a master joiner might even be a master builder—or, to use another word for the same thing, an architect. And with such a varied and broad engagement in the great cooperative art of architecture, the joiner joined not only “pieces of wood” but the whole vast and varied range of trades necessary to building, from the basic structure to its finest details including its painted details. Such work brought what we today might consider an ordinary laborer, specialized and therefore likely to be narrow-minded and hide-bound, in very practical and meaningful touch with a great variety of tradesmen and their varied talents and experience.

And at this point all the implications of the work of the joiner and of the name of the his trade begin to come in to focus. In a world that seems to build willy-nilly driven by a lust for private property, we have forgotten the public nature of architecture. Not only civic and ecclesiastical but all buildings, unless they’re isolated from public sight, are part of the common landscape and public realm. When building not only a town hall or a cathedral but also the humblest home and shelter, the joiner’s own work typically engaged him in public and communal life—in the work of framing civitas and civilization itself.

So when we take the time to acknowledge the nature of the joiner’s real work and recognize the joiner’s great scope of engagement, the name of his trade begins to apply on the social and communal level as much as it does in relation to “pieces of wood.”

But as we peer longer through the joiner’s window and begin to appreciate the joiner’s work of assembling with care not merely windows and picture frames but the world, we see that a parallel comprehensiveness extends to creative and intellectual complexity and joins the whole being—head, heart and hand—of the laborer himself. Inherent to the work, apart from deliberately decorative treatment such as carving, is much more than mere functional and utilitarian purpose. There’s the engagement of reason and pursuit of beauty—and the continual revelation of how the two are joined to each other and engage, strengthen and ennoble the mind and heart of the laborer.

Even the simplest joinery demands some real thought, some engineering. And the concern for fitness—beginning with how joints fit together, the appropriate relation of different members, and extending to strong and proper and thus appealing proportion and composition and above all practical functioning of the structure—is, as William Hogarth said in The Analysis of Beauty, the first criterion of beauty. “When a vessel sails well, the sailors always call her a beauty; the two ideas have such a connexion!”

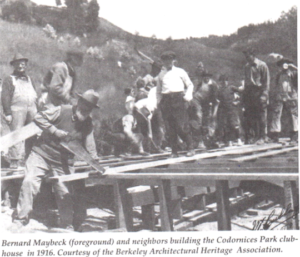

Berkeley’s great architect Bernard Maybeck at the joiner’s trade, knowing that beauty is rooted in workmanship.

Even a nailed joint done with great care can be appreciated for its beauty. Not long ago I met the son of a contractor, Frank Pennell, who’d worked with the famed Berkeley architect Bernard Maybeck, and recalled his father’s story of visiting a job site with Maybeck to inspect the house’s just-completed framing. Maybeck was struck by the beautiful workmanship, admiring in particular the perfectly mitered and nailed bracing of the studs. And he said to the contractor, “Forget about the paneling we planned to put on the interior walls. I want to be able to see this framing. Just fill in between with plaster and leave the studs exposed.”

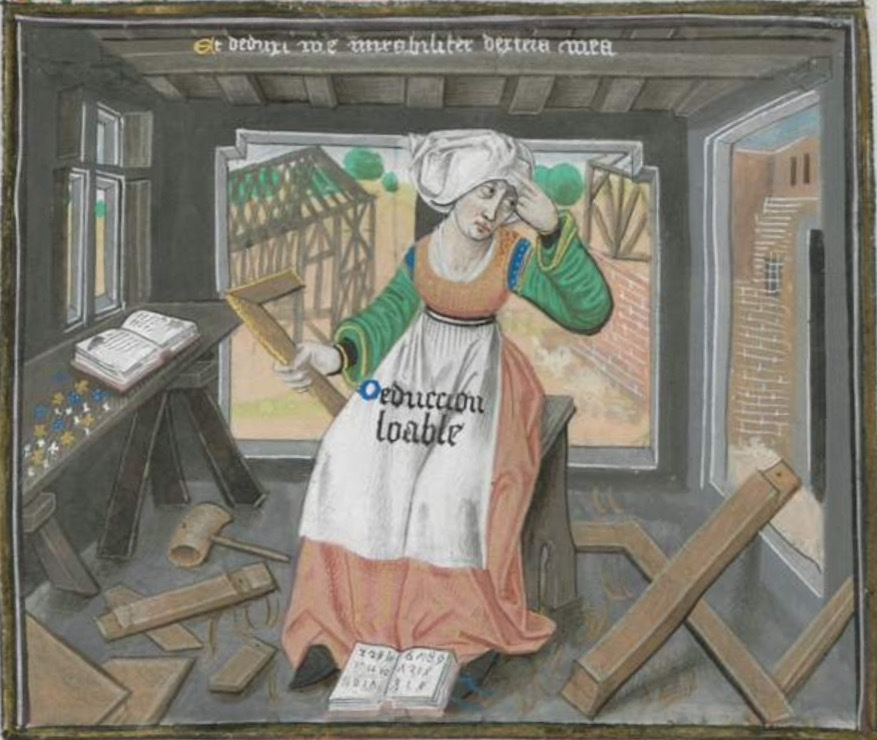

This admiration for and understanding of the artistry inherent in what might seem to be the purely utilitarian work of the joiner couldn’t be better portrayed than it is in this medieval manuscript illustration, below, of an intellectually engaged joiner, flowers on her bench, and its accompanying poem. (And, as this image shows, the joiner’s trade was not the exclusive domain of men.)

The Lost Art Press blog, where I found this, explains:

Sometime between 1463-1464 George Chastellain, Jean de Montferrant and Jean Robertet exchanged poems and epistles that eventually became a manuscript titled, ‘Les Douze Dames de Rhétorique’ (The Twelve Ladies of Rhetoric). Each branch of rhetoric features a poem and the image of a woman symbolizing the branch.

The woman symbolizing Deduction is shown in a carpenter’s workshop and in the background is a construction site. With her hair covered and wearing an apron Deduction is dressed as a woman that would be found helping out in the family workshop. In her role of explaining her branch of rhetoric and the scene in which she is set, she points to her head with one hand while holding a set of tools (square, dividers, plumb) in the other hand.

In her poem she explains: “Without a doubt I arrive late and I am slow to speak to merit an important place in this august assemblage. But, I am relevant, I function and I am quite useful for the completion of any beautiful work. Once it is assembled, one must give it a title because the more a work stands out for its rich materials and beautiful appearance, the more I apply a prudent hand to bring it glory and title.”

Here is pictured an exemplary frame-maker, no mindless drudge but the very symbol of reason, in the midst of joining a frame, vigorously engaged in the intellectual challenge and—inseparable from that—the beauty of her work. Obviously part of a larger building project, the phrase “august assemblage” suggests she is not only one with “The Twelve Ladies of Rhetoric” but with all the cooperative trades involved in and necessary to architecture and the community the structure will serve.

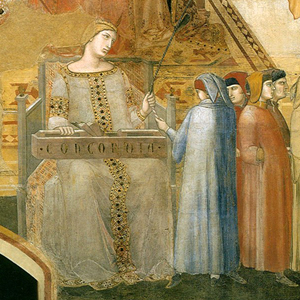

Detail of Lorenzetti’s mural, 1338-9, in Siena’s Town Hall, showing “Concordia” (harmony) holding a joiner’s hand plane

And just how far can we see in this wide world opened up to us by the joiner’s window? That should probably wait for a longer essay, but here are a few images that reveal the profound scope of significance, meaning and nobility in the work of the joiner. At right is a detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fourteenth century murals in La Sale de Pace, or the Room of Peace in Siena’s medieval Town Hall. Called “Allegory of Good and Bad Government,” the murals include, at the foot of the figure of Justice, the beautifully attired woman symbolizing the true harmony of a town governed justly—her meaning made clear by the joiner’s plane in her lap on which is written “Concordia,” or concord, i.e., harmony.

If such harmony of justice and kindness—the message of the Golden Rule—is the great lesson of all true religions, it should come as no surprise to remember that Christ was a carpenter, a joiner of humanity and just civilization. As Ananda Coomaraswamy observed in his book Christian and Oriental Philosophy of Art, “Our study of the history of architecture will make it clear that ‘harmony’ was first of all a carpenter’s word meaning ‘joinery,’ and that it was inevitable, equally in the Greek and the Indian traditions that the Father and the Son should have been ‘carpenters,’ and show that this must have been a doctrine of Neolithic, or rather ‘Hylic,’ antiquity.”

- Christ cutting a tenon

- Christ cutting a mortise

- Christ sawing a plank

- Vishvakarma, the Hindu god, is principal architect of the whole universe.

The Demise of the Cabinetmaker’s Frame and the Degradation of the Joiner, Carver and Artisan

Over a period of centuries, even before people stopped recognizing that breed of workman called a joiner, what had been called the art of the joiner became reduced to the craft of the joiner. Implicit in this linguistic re-framing was the spreading notion that such labor was relatively mindless—mechanical and purely utilitarian, rather than creative, spiritual and intellectual.

This division and distinction between artist and artisan was part of the transformational explosion of division of labor instrumental to the industrial revolution. Initially, increased division of labor was manifested in specialization of different workers employed under one roof—an arrangement that preserved the fellowship of different trades and thus their mutual respect. But at least in the frame-making trade, such specialization was followed by a separation that brought with it a significant and new kind of inequality marked by a denigration of the “mere” artisan—and commensurate denigration, degradation, and debasing of the art of the picture frame.

This process of degrading the joiner’s role in frame-making is succinctly captured by former National Portrait Gallery frame curator Jacob Simon in his 1996 book, The Art of the Picture Frame. According to Simon, in the early 17th century, “Framemaking…was a partnership between the joiner, the carver and the gilder. The basic framework was the task of the joiner.” By the mid-18th century, though, the role of the joiner was being described in the pages of The London Tradesman this way:

This process of degrading the joiner’s role in frame-making is succinctly captured by former National Portrait Gallery frame curator Jacob Simon in his 1996 book, The Art of the Picture Frame. According to Simon, in the early 17th century, “Framemaking…was a partnership between the joiner, the carver and the gilder. The basic framework was the task of the joiner.” By the mid-18th century, though, the role of the joiner was being described in the pages of The London Tradesman this way:

There are a set of Joiners who make nothing but Frames for Looking Glasses and Pictures, and prepare them for the Carvers. This requires but little Ingenuity of Neatness as they only join the Deals roughly plained, in the Shape and Dimensions required. If the Pattern chosen for the Frame is to have any large Holes in it, these they cut out in their proper places, or, if it is to have Mouldings raised in the wood, they plant them on; but they leave the Carver to plant on the rest of the Figures. But we have said enough of this Trade, who is no more than a cobbling Carpenter or Joiner.

“We have said enough of this trade”—with that, the once universally honored joiner was dismissed. He was a mere artisan, a practitioner of one of the old arts. And in the new order his place was apart and away from “Art.” The frame was less well joined (who would know, since its corners were hidden by gold and plaster, that nails, not dovetails, held it together?). And the frame, once fully integral to the painting, was increasingly interchangeable and eventually optional altogether.

Nineteenth century boxwood compo molds (from Paul Mitchell’s website)

If, as in this account, the carver enjoyed more respect and prestige than the lowly “cobbling” joiner, his demise under the new order came soon enough—as one might expect in a trade that was resorting to “planting on” decoration. Where carving had once been real and integral both to the cabinetmaker’s art and to the wooden members of the frame (just as the joiner, true to his craft, had given real integrity to the frame through the proper joinery of its members to each other, not with nails but mortise-and-tenon joints, dovetails or lap-joints), a new material called composition, or compo, came along to replace it. A fine hard plaster molded and “planted on” to impersonate carving, compo “was said to be at least eighty per cent cheaper than carving,” according to Simon. (No wonder the French called it “pate economique”—economical paste!) “Within a generation of its introduction in the late eighteeenth century, Thomas Martin could write, ‘There are only eleven master carvers in London, and about sixty journeymen (though at one time there were six hundred), many of these latter are now very old.'”

Frames of the late 18th century might have looked much like those from several decades earlier, but they were, underneath, something much shoddier. Framer and frame historian Paul Mitchell points out that, “Rather than executing a single frame in the form of a unique sculptural work, carvers were now required to produce the wooden moulds for applied compo ornament“—effectively being hired to dig their own graves. If such division of labor had benefits for mass production and thus lower-priced goods, it’s easy to see how such industrialization meant above all the production of what Morris liked to call “makeshift.” Integrity and substance were sacrificed to superficialities of surface decoration (hence the term “plant on”). With respect to the frame, the degree of quality was evident in inverse proportion to the degree of arrogance, pretentiousness, and showiness.

Above all, though, the compo frame serves as a perfect window on the division between “art” and “craft,” between “artist” and “artisan.” Where once all artist/artisans had appreciated the frame as “a unique sculptural work” and an art form to take seriously as a worthy companion, if not an equal, with painting, within a few decades its fortunes had completely changed. “The Arts” had become “Art” (as Larry Shiner’s excellent book The Invention of Art demonstrates), and “Art” had become almost exclusively the art of painting. Although new and cheaper printing techniques (and much later photography) were certainly examples of applying “labor saving devices” and utilitarian industrial processes to the production of pictures, the fate of the painter was anything but one of obsolescence. As the standing and prestige of the frame-maker, the joiner, and all artisans fell, the prestige of the “fine artist” rose. Now seen as the exclusive possessor of a special and mysterious kind of manual and inventive genius, he’d become the exclusive holder of the title of “artist.” Whereas all the trades had been considered arts—all entailing imagination, intellect and intuition—that diverse and popular realm now stopped abruptly at the edge of the canvas. The frame-maker was no longer a brother to the painter. The mechanization and industrialization of the art of the joiner/carver/frame-maker meant the extraction of invention, intellect and instinct from his work and a new apotheosis of the painter, believed to hold those qualities in extraordinary measure.

John Hill (ca. 1780-1841), “Interior of the Carpenter’s Shop at Forty Hill, Enfield,” 1813? Oil on canvas, 18-1/2″ x 27″. The Tate Museum

Still, the joinery, if you will, of artist to artisan was tenacious enough that, from the first signs of the two coming apart, it would take centuries to reach the severe division we have now. Ruskin dated its onset to the time of Michelangelo; but severance was not complete, according to Larry Shiner in The Invention of Art, until the early 19th century. The painting above, done about the same time as George Forster’s, shown earlier, and similar to it, is interesting in this light because it was done by a self-taught painter, John Hill, who was also a joiner. According to the Tate, “it almost certainly depicts John Hill’s own workshop or that of his father Thomas Hill (d.1814), also a carpenter.” No surprise, then, that at the very center of the composition, hanging on the back wall (next to a beautifully composed “landscape painting”—the view out the shop window), is what looks like a picture frame. But his painting is above all a painter’s work of praise for his other trade. Again, artists, even in their own specialized arts, understood the nobility of the arts generally—the eternally wonderful productive and constructive human powers which, after all, built and sustained civilization.

Reviving the Art and Craft of the Cabinetmaker’s Frame

I’m glad to see that Wikipedia’s entry for “Joiner” no longer says the term is obsolete in the U.S.A. Nonetheless, given the triumph of Ikea and makeshift cabinetry and furniture, and more largely the denigration of labor the world over, the note seemed like something more than merely a difference in American and British vocabulary. It’s a glaring indication of our lost understanding of the arts and of who and what an artist is. As demonstrated by countless lectures concerned with, and more than once titled, “Art and Labor,” re-joining the two, reuniting the artist and the artisan, and restoring the primal unity of all the arts, was the core concern of the Arts and Crafts Movement. “Art is the expression of man’s joy in his labor,” William Morris famously said (paraphrasing John Ruskin). As a craftsman, Morris was primarily known as a weaver. But to his first biographer, JW MacKail, that was only one indication of his fundamental nature and aspiration. Morris was a man, MacKail said in the book’s introduction, “the whole of whose extraordinary powers were devoted towards no less an object than the reconstitution of the civilized life of mankind.”

I’m glad to see that Wikipedia’s entry for “Joiner” no longer says the term is obsolete in the U.S.A. Nonetheless, given the triumph of Ikea and makeshift cabinetry and furniture, and more largely the denigration of labor the world over, the note seemed like something more than merely a difference in American and British vocabulary. It’s a glaring indication of our lost understanding of the arts and of who and what an artist is. As demonstrated by countless lectures concerned with, and more than once titled, “Art and Labor,” re-joining the two, reuniting the artist and the artisan, and restoring the primal unity of all the arts, was the core concern of the Arts and Crafts Movement. “Art is the expression of man’s joy in his labor,” William Morris famously said (paraphrasing John Ruskin). As a craftsman, Morris was primarily known as a weaver. But to his first biographer, JW MacKail, that was only one indication of his fundamental nature and aspiration. Morris was a man, MacKail said in the book’s introduction, “the whole of whose extraordinary powers were devoted towards no less an object than the reconstitution of the civilized life of mankind.”

And for a profound appeal to the spirit of Labor Day, I’d offer another wise word from WR Lethaby:

As work is the first necessity of existence, the very center of gravity of our moral system, so a proper recognition of work is a necessary basis of all right religion, art, and civilization. Society becomes diseased in direct ratio to its neglect and contempt of labor.

That is very fine joinery of labor to humanity’s higher aspirations. But to grasp the significance of the humble joiner to that lofty thing we mean by the word “Art,” just pick up Webster’s dictionary and read that word’s etymology: “Origin: Middle English, originally from the Latin ar-, to join, fit together.”

Such discoveries suggest the dignity earned and honor deserved by the too-often-ignored labor of the joiner. We consider it our mission at Holton Studio to restore some of the old understanding and appreciation of the work of the joiner, so crucial to the art of the frame—and to the place of the arts, not ultimately in museums or galleries (though we have one of our own) but in the home, joined with all the other arts, including the fine, pictorial arts of painting, drawing and printmaking, that frame daily life. We honor in our work every day the labor and the art of the joiner. And we remember especially on Labor Day the countless worthy joiners—and all laborers, “drawers of water and hewers of wood”—who, as scripture says, “maintain the fabric of the world.”

« Back to Blog