In tumultuous times as these, you’ve got to take the long view. And that’s what we’ve been doing—in more ways than one. We’ve had the honor and privilege to frame this extraordinary and very long 16th century map with a story that’s also long, reaching back, by way of the middle ages, all the way to the first century BC and the Roman Empire that it depicts. The engraving, dated 1598, is the culminating work in the life of the great Renaissance Dutch cartographer, Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)—although not his crowning work; that would be Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, the first modern atlas.

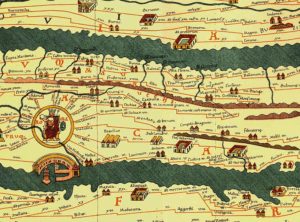

The four panels are each about 8″ x 41″, and framed and hung together they extend almost fifteen feet. Forming a continuous map, the panels span the Roman Empire from Great Britain to India. More on the map and its fascinating history are below.

The four panels are each about 8″ x 41″, and framed and hung together they extend almost fifteen feet. Forming a continuous map, the panels span the Roman Empire from Great Britain to India. More on the map and its fascinating history are below.

The Frame

The frame, which took around 90 hours, all told, is the polyptych cassetta I showed in its final stages in a post a couple of weeks ago, here. Made in quartersawn white oak, with Medieval Oak stain, it’s 3-1/2″ wide—the vertical side members are slightly more—and is composed of a mortise-and-tenon flat and carved cap and sight moldings. The sight mold is carved with beads in a pattern mimicking those of the printed border of the map. I also posted about that earlier, here. The design is finished off with an 1/8″ slip gilded in 23 kt gold leaf.

Left end of set, showing cartouche. (A translation can be found here. More history below.) Click for large view and to see border from which carved bead pattern is drawn.

The length of the whole thing, of course, presented a real framing challenge. Fortunately, the fact that it was in four separate panels allowed us to frame each panel individually, but in a fashion allowing the frames to be butted up to each other to present as a unit. (Scroll down for more process pictures, including ones of how the frames are aligned and hung on the wall.)

History of the map

The story behind the map is as remarkable as the map itself. It is copied from the 13th century Tabula Peutingeriana, or Peutinger Table, created by a monk in Colmar, Alsace (modern-day France) in 1265. At 13 inches high and over 22 feet long, the Peutinger Table is, according to Wikipedia, “thought to be the only known surviving map of the Roman cursus publicus, the state-run road network.” (It’s now preserved in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. In 2007, this earlier map was placed in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.) But the history of Ortelius’s Renaissance map actually goes back even further than the medieval Peutinger Table, which itself was based on a map commissioned in the first century BC by the Roman general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa during the reign of the first Roman Emperor, Augustus.

Thus, we have before our eyes not only a direct connection to the Renaissance, but a view of the world with direct lineage to antiquity—and a rather humbling window into ancient civilization.

Neither the Peutinger Table nor this Renaissance copy are, as you can see, conventional maps in the sense of being attempts at accurate geographical representation; but are distorted, especially latitudinally, to suit a more schematic purpose of indicating roads, landmarks and distances (which are, in fact, fairly accurate). This, I suppose, is why it’s called a “table.” If not quite so impressive in length as its medieval original, at about 14 feet long, Ortelius’s copy is a remarkable work which impresses one with the vast size of the Roman Empire—no doubt the intent of the imperious Romans who were responsible for the original.

Ortelius

Though he died before the work was completed, Abraham Ortelius supervised the engraving of the map, making it the final achievement of an illustrious and eventful life spanning the so-called Age of Discovery, the Reformation, and the first three decades of the Eighty Years War—which included the horrific 1576 Sack of Antwerp, Ortelius’s home. In addition to creating the first modern atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theater of the World), Ortelius is believed to be the first person to hypothesize continental drift—the now accepted theory that the continents were once joined before drifting apart to their present positions.

Orteliusmaps.com has the following historical sketch of the map we framed, and fills in how the medieval version came to Ortelius:

Phillip Galle’s 1579 portrait of Ortelius (obviously the source of Rubens’s posthumous portrait, above) is captioned “Ortelius gave the mortals the world to admire and Galle gave the world Ortelius to admire.”

[A]s early as 1578, Ortelius knew about the existence of a series of manuscript road maps, showing the Roman view of the world at around the third century [the Wikipedia entry indicates scholars now believe its sources are earlier]. The original, found by Konrad Celtes (1459-1508) in a library in Augsburg, came into the hands of Konrad Peutinger (1465-1547) and later went to his relative Mark Welser. Welser was the first to publish a copy of it in 1591 at Aldus Manutius in Venice. Ortelius found this copy inadequate. Therefore, in 1598 new manuscript copies were made at his request by Welser. [This significant role of Welser—”Marco Velsero”—explains the prominence of his name in the cartouche.] The present set of eight (adjacent) maps on four sheets were engraved following these copies. The original Peutinger maps disappeared, were retrieved in 1714, and are now in the Vienna National Library. Because of damage and progressive blackening of the 11 (once 12) sheets of parchment, Ortelius’ version is now the most reliable representation. Ortelius supervised the engraving, but did not live to see the result, which was first published separately in 1598 by Moretus.

More resources on the map’s history can be found at the bottom of the post.

Fitting and hanging the maps—

Fitting—

Fitting—

For the maps to be framed archivally, the frame rabbets were cut wide to accommodate gasket rag mats which separate the prints from the glass and also allow them to shrink and expand. The rabbets were lined with a metal barrier tape to keep the acids in the wood from migrating into the prints. Museum Glass was used. Sam Edie did the expert fitting (as well as most of the photography for this post).

Hanging—

- Cleats ready for panels

- The separate panels before hanging

- One…

- …two…

- …three…

- …quick close up of third panel (aligning dowel visible at the bottom end)…

- …four—and done!

Resources on the map’s history—

Wikipedia has good entries on Abraham Ortelius and the Peutinger Table. An excellent short video on the Peutinger Table can be seen here. A much longer scholarly article, “The Medieval and Renaissance Transmission of the Tabula Peutingeriana,” is here.

Earlier posts on this project—

My post about carving the beads is here, and another post showing the cap molding being carved, the glue-up and finishing is here.

My post about carving the beads is here, and another post showing the cap molding being carved, the glue-up and finishing is here.

Spectacular framing, and a marvelous story about Ortelius’s map—congrats to all!

Tim,

Your hand-carving is always a subtle show of virtuosity, while the design and architecture of the frame are where artistry and experience are felt. Masterful.

And your blog posts on this project are delightful. It’s fun to see the work that you and Sam do documented with so many behind-the-scenes photos, and it’s equally fun to read your summary of the fascinating story behind these pieces of paper.

A one-of-a-kind achievement. Thanks for sharing this!

That is just great! All around,