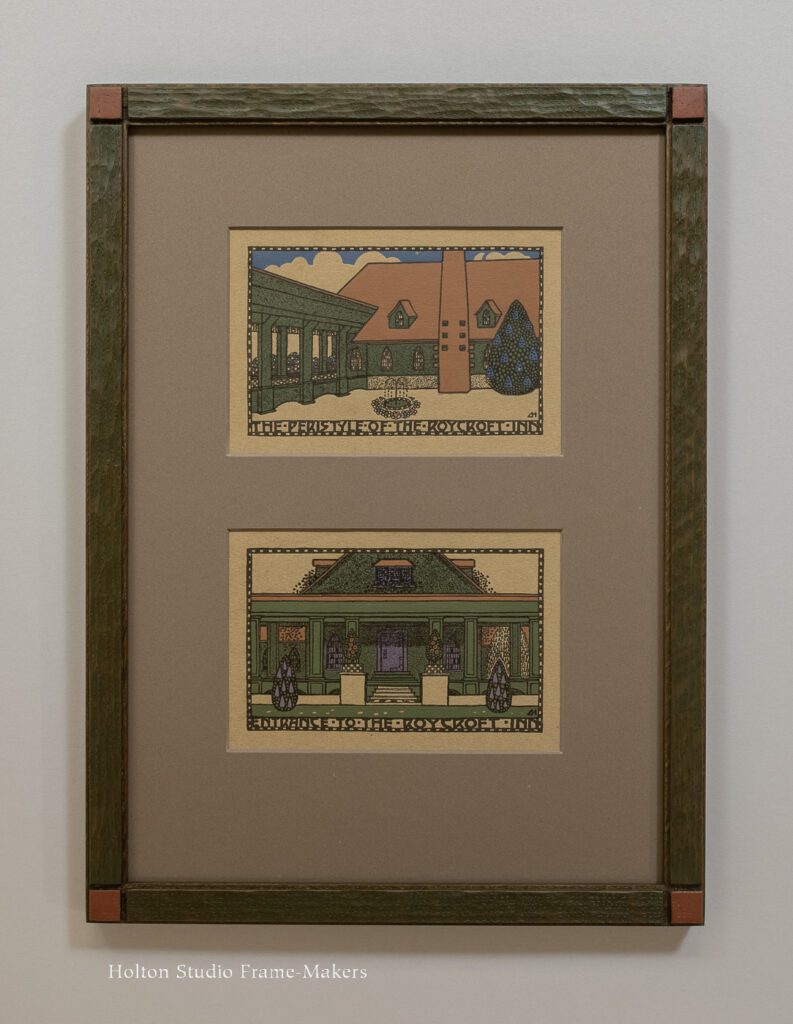

This is a set of six hand-colored prints by Dard Hunter (1883-1966), framed in pairs. Made in 1909-1910, they depict the architecture of the Roycroft campus in the heyday of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Dard Hunter was a major Arts and Crafts figure, especially in the realms of graphic design and printing.  So for me, as a great believer in that movement, it was a treat to get to frame these.

So for me, as a great believer in that movement, it was a treat to get to frame these.

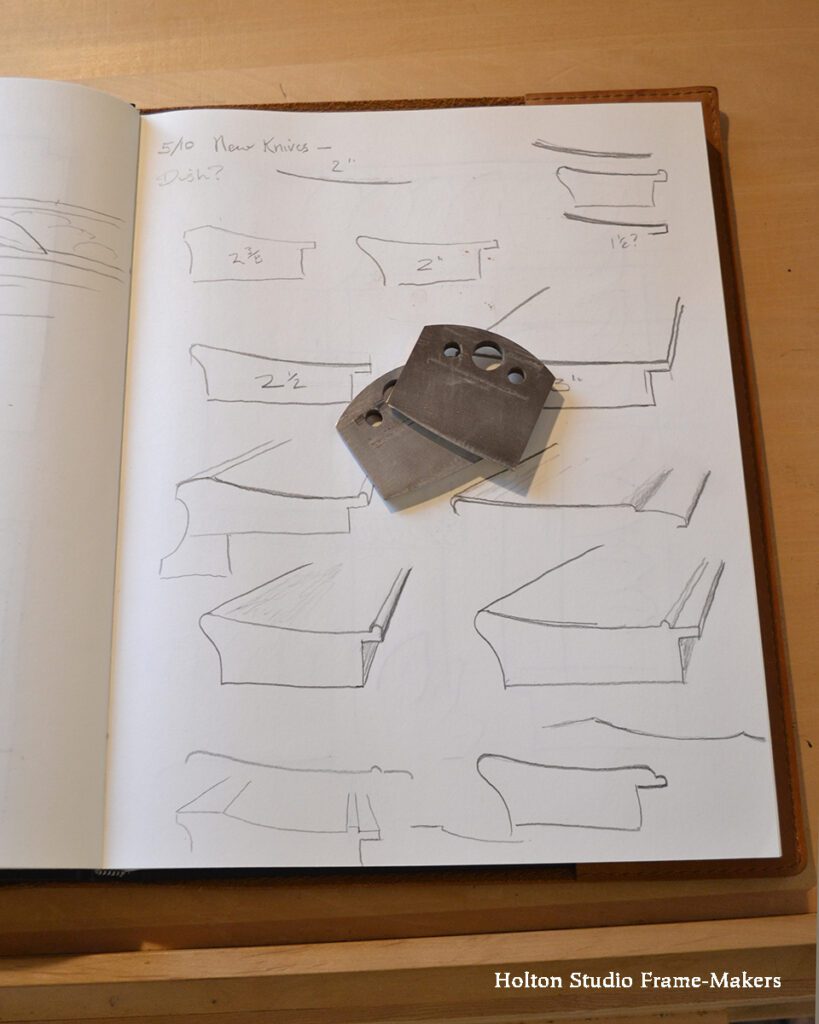

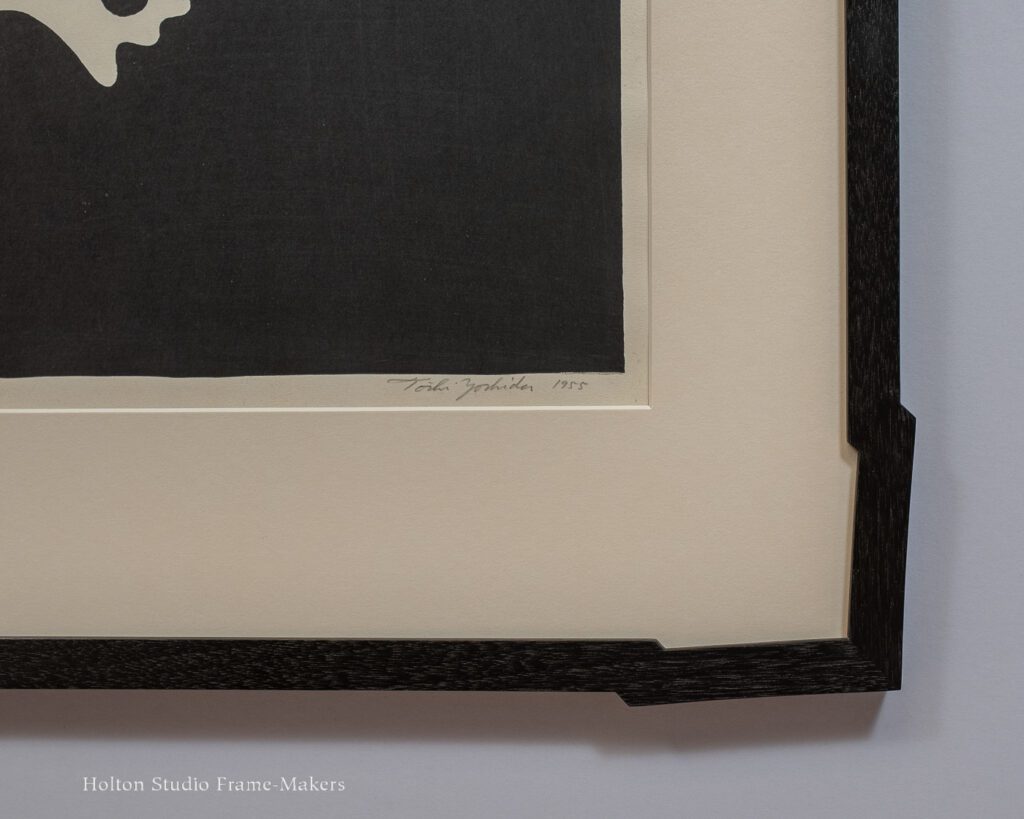

Each image is about 3-1/4″ x 5-1/4″. The fumed quartersawn white oak frames are 3/4″ wide. Their outside dimension are 15″ x 11″. The frame design follows the obvious cue provided by Hunter’s borders of little squares. The profile is our No. 15, which we embellished with some carving and painting: squares carved at the corners (a simpler version of this design is shown at right), the panels between the corners gouged for some texture, and then those panels and the corner squares painted in complementary green and red to celebrate Hunter’s vivid coloring. Trevor made the frames, and Sam and Avi finished them.

Dard Hunter

Dard Hunter III of Dard Hunter Studios writes that in 1903, his grandfather’s eyes were opened to Arts and Crafts architecture by a stay at The New Glenwood Hotel—now The Mission Inn—in Riverside, California. Soon after, he offered his services to the prominent Arts and Crafts leader Elbert Hubbard and joined Hubbard’s Roycroft community in East Aurora, NY. There, swept up in the spirit of the movement, he explored a range of arts, including furniture, stained glass, pottery, and jewelry, as well as the book arts he would later focus on, securing for himself an enduring legacy as one of the most important modern figures in that field. (In his lifetime, he wrote an incredible twenty books on papermaking, for example.)

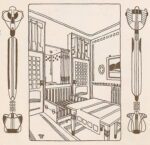

Hunter also took to perusing “journals such as Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, gaining a sense of design in the Viennese fashion,” according to Dard III. When Hunter married pianist Edith Cornell in 1908, “he was so enamored with the work of Josef Hoffman and the Wiener Werkstatte that they spent their honeymoon in Vienna. For the next few years, Hunter incorporated the geometric patterns and highly stylized figures into his work with the Roycrofters.” You can see the influence on Hunter of Hoffman’s interior drawings shown at the bottom of the post.

These prints, then, are an important expression of international cross-fertilization in the history of the Arts and Crafts Movement in America. They also point to the significance of architecture in the Movement, and its place at the heart of Arts and Crafts ideals—the mother of the arts under which they are all practiced. Framing depictions of architecture always carries special opportunity for harmony between the pictorial subject and the architecture of the frame. But in the case of these images of the iconic Arts and Crafts campus of the Roycrofters, imbued as it is with the unifying ethos of the Movement, that’s especially true.

Below are interior designs by Hoffman, clearly showing his influence on Hunter. In particular, note Hoffman’s fondness for patterns of squares.

Learn more about Dard Hunter at Dard Hunter Studios. (Dard III’s excellent short biography is here.) If you’re ever in the vicinity of Chillicothe, OH, south of Columbus, it’s worthwhile visiting Dard Hunter’s home, Mountain House to see the wonderful museum Dard III has set up in tribute to his grandfather.

Learn more about the Roycroft community here and here. And watch PBS’s “Head, Heart, and Hand: Elbert Hubbard and the Roycrofters.”

—Tim Holton