Suitable frames for tiles are hard to come by—especially as the old tiles in particular become more highly treasured: folks want to do them proud, but production frames on small works of real handcraft only accentuate their makeshift nature. Yes, tile frames are easy to overdo, and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with a totally plain frame. But tiles are highly architectural, which makes them similar to paintings in being able to hold up to substantial frames. Having relief helps them in this respect as well. I want to show a few examples of what can be done with an exceptional tile that you might want to feature in your home with a frame that both protects and suitably honors it. It’s also an opportunity to demonstrate what a single key design element can do for any piece of art.

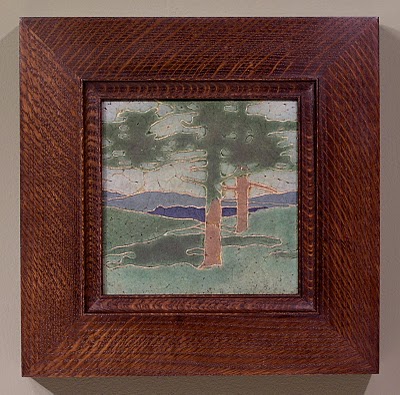

This first piece, above, is a Grueby tile—a great and iconic Arts and Crafts piece familiar to many. At just 6″ x 6″ it wanted a restrained treatment. The fine line work suggested the two fine beads for the sight edge of the frame, while the cove (between the beads) provided a gentle means of focusing the eye on and taking the viewer in to the quiet mood of the piece.

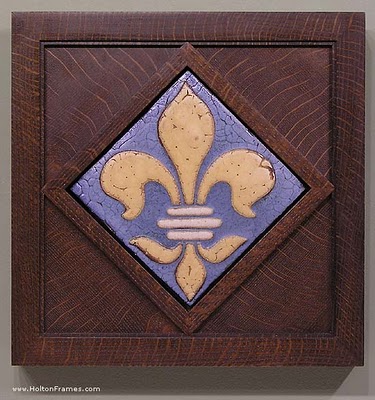

The second example is another Grueby piece—an insignia tile in a diagonal format which offered an enjoyable challenge. We focused on the format of the of the piece to suggest an interesting design. This is two mitered frames with floating panels in the triangular spaces. I had fun using the ray flake to create kind of a sunburst effect.

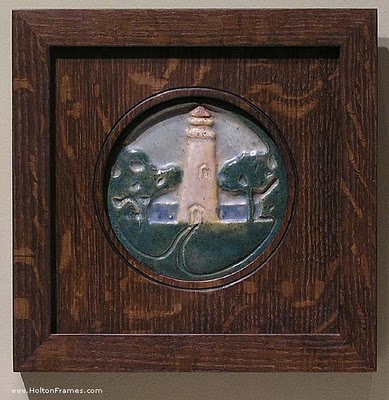

The third example is a round trivet tile with a scene rendered in carved lines. Trevor expertly carved a line of the same size and shape (a small flute) just outside the circular window.

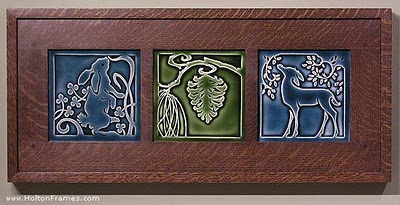

The series here is contemporary, made by Carreux de Nord out of Wisconsin. The wonderful line work in these needed only a complementary rectilinear treatment of the frame. A mortise-and-tenon flat was used for its architectural character and to enhance the horizontal format of the tiles. This frame in particular could be hung to achieve great mural feeling. A mitered cap molding was chosen to contain and delineate the whole composition. What beautiful work these tile makers do!

Finally, another mortise-and-tenon frame we made years ago for a Rookwood Thistle tile. Again, the frame couldn’t be simpler, except for the chamfer that amplifies the lines of the tile.

Of course, in all these examples, beautifully flaked quartersawn oak provides a great deal of interest as well as suitable material for Arts and Crafts items and the homes they’re likely to reside in.

All these frames are flat, in keeping with the decorative flat treatment of the tiles, relying on just one element in the frame to echo a key element in the tile. But that’s enough to achieve the frame’s goal of sustaining and expanding the spirit of an artwork into the architectural realm and the life of the setting in which it will take its place.