“We get through with a canvas. Then what do we do? We turn it over to some fool who puts it into a hideous gold frame and kills our every last effect.” —the character of Georges Seurat in Irving Stone’s novel, Lust for Life

“FRAMES—None but gold frames can be admitted.” —1848 statutes of the Royal Academy

“[A] very prevalent error is to set almost all pictures in frames gilded all over,” complained an art critic in the pages of the trade magazine The Cabinet Maker and Art Furnisher in 1883. “Few pictures are of such brilliance as to be able to bear such a mass of bright gold without detriment to their effect.” The article was a review of a show at London’s most reform-minded gallery, and offered hope for changes in how paintings would be framed:

Some artists are taking a healthy departure in the direction of using frames other than gilt. One or two instances of this may be seen in the present exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery, notably Mr. [George] Clausen’s study of a girl’s head. The frame is a bold hollow moulding of dark walnut, with a beading of gold next to the picture, the delicate cool colouring of the canvas is enhanced by this frame, while in a gilded one it would have been lost, and the picture would probably have appeared insignificant.

Unfortunately, efforts such as George Clausen’s did little to change exhibition rules in Britain. And in the U.S. too, for decades to come the gold frame convention would continue to rule the day—and to irritate and anger painters. In 1899, Thomas Eakins had a painting to submit to an exhibition at the Carnegie Institute. Wanting to frame the portrait in dark wood, he had to check whether the Institute enforced “a hard and fast rule that frames must be gold… I could still have the frame gilded or gold painted temporarily for exhibition purposes,” he wrote in a letter, “but I always protest against the barbaric splendour of new gold frames which injure all paintings.” Even today, while exhibition requirements are gone, a visit to almost any gallery or museum displaying realistic paintings proves that the gold frame convention continues to govern institutional and commercial preferences. As the above quotes suggest, however, the notion that gold settings are always the most suitable has been far from universal, especially among artists. Fortunately, according to several gallery owners I’ve talked to, there has been in the last couple of decades a noticeable cooling of the public’s preference for gold frames in favor of natural dark wood ones.

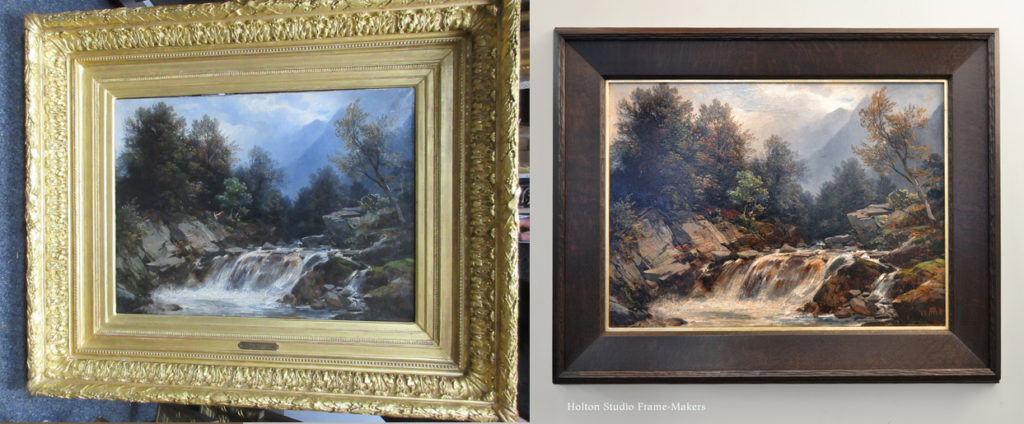

The cabinetmaker’s frame tradition that we work in offers a beautiful, sound and more humble alternative to the widely deplored but deeply-entrenched convention of setting paintings in gilded frames. Below are “before and after” shots of paintings that arrived at the Studio in gold frames which customers wisely sought to replace with our hardwood frames. “A gilt frame is intended for show,” writes National Portrait Gallery frame historian Jacob Simon. Our approach, however, is founded on the common sense belief that a frame’s real job is to help people see the picture — keeping in mind William Morris’s timeless phrase and guiding words for every artist and designer: “for beauty’s sake and not for show”.

The examples here demonstrate the dramatic contrast between the conventional gold frame and the cabinetmaker’s alternative—and how we might correct a “very prevalent error”.

William Keith, “Sentinel Rock,” 1872. Oil on canvas, 18-1/4″ x 14-1/4″. More…

.

Christian Jorgensen (1860-1935), “Yosemite Valley,” 1910. Oil on canvas, 42″ x 72″. More…

.

Virgil Williams, “California Farm Scene,” 1884. Oil on canvas, 10″ x 20″. More…

.

.

.

.

William Keith, “Mount Hood,” n.d. Oil on canvas, 16-1/2″ x 31-1/2″. More…

.

Percy Gray, “California Hillside,” 1914. Watercolor, 11″ x 15″. More…

.

Joseph H. Sharp (1859-1953), “Hunting Son—Taos Indian,” N.d. Oil on canvas, 20″ x 16″. More…

.

.

Alexander Max Koester (1864 – 1932), “Ducks In a Pond,” no date. Oil on canvas, 31″ x 52″. More…

.

.

David Mann (b. 1948), “Red Lodge Smoke,” no date. Oil on canvas, 24″ x 20″. More…

.

.

.

.

Thomas Hill (1829-1908), “Study for Boulders, Yosemite,” n.d. (1880’s?). Oil on canvas, 15″ x 22″. More…

.

H.D. Gremke (1860-1939), “King’s River Scenery”, ca. 1900. Oil on canvas, 12″ x 10″. More…

.

.

Arthur Parton (American, 1842-1914), “Fishing Scene,” 1887. Oil on canvas, 24″ x 18″. Framed in Compound Mitered Frame No. 308.2—3/4″ + Cap 811—7/8″, in quartersawn white oak (Dark Medieval Oak stain), with gilt slip.

.

Dana Bartlett, (1882-1957), untitled California landscape, n.d. Oil on canvas, 11″ x 14″. Framed in Compound Mitered frame No. 108.1 CV—2-3/4″ + Cap 400 CV—7/8″. More…

.

.

Benjamin Williams Leader, “The Wetterhorn from Rosenlaui,” 1875. Oil on canvas, 72″ x 60″. More…

.

.

.

.

.

.

Rosa Bonheur, oil on canvas, 10″ x 8″. More…

.

.

William Keith (1838 – 1911), “Lady with a Hat”, ca. 1884. Oil on canvas 17″ x 14″. More…

.

Joseph Lorusso (b. 1966), “With Attitude,” n.d. Oil on canvas, 12″ x 12″. Framed in No. 134.1—3″.

.

Thaddeus Welch (California, 1844-1919), (California landscape), no date. Oil on canvas, 14″ x 24″. More…

.

.

.

Grace Carpenter Hudson (California, 1865-1937), “Help On the Dow,” 1898. Oil on canvas, 16″ x 24″. More…

.

Arnold Friberg (1913-2010), “The Eyes of Chief Joseph,” 1975. Oil on canvas, 36″ x 51″. More…

.

.

.

Dwight Clay Holmes (Texas, 1900-1986),“Red Bud”. Oil on canvas, 20″ x 16″. More…

.